Discussion has grown for months about how the upcoming U.S. election results could be contested and possibly subverted.

No one knows for certain what will happen, but there are precedents we can learn from about how attempts to overturn election results have been stopped. Four cases in recent decades—one in Southeast Asia, one in Africa and the other two in Eastern Europe—involved an incumbent president or party attempting to steal an election only to have it reversed through large-scale nonviolent direct action. This article looks at these cases, and identifies key lessons.

Philippines, 1986

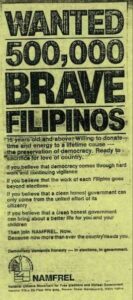

Newspaper ad, “Brave Filipinos wanted: 15 years and above. WIlling to devote time and energy to a lifetime cause: The preservation of democracy.” Source: NAMFREL Facebook page.

Ferdinand Marcos was elected president of the Philippines in 1965 and re-elected in 1969, both by popular vote. However, he declared martial law in 1972 and subsequently ruled with dictatorial powers. Extrajudicial killings, torture, and disappearances were widespread. He enjoyed close relations with the United States, which provided arms and training to his security forces. Following the assassination of opposition leader Benigno Aquino in 1983, popular demands for a free and fair presidential election increased. At the end of 1985, Marcos called for a snap election to take place early the next year on February 7. The opposition united behind Aquino’s widow, Corazon Aquino.

The National Citizen’s Movement for Free Elections (NAMFREL) mobilized 500,000 volunteers to monitor the most sensitive and vulnerable precincts in an effort to minimize violence and electoral fraud and conduct its own vote count. NAMFREL displayed charismatic leadership, organization, and discipline, in part through its nonpolitical, mass training sessions during the period leading up to election day. Trainers in nonviolent action led NAMFREL volunteers in role plays involving ballot box snatching, irregularities in vote counting, and other scenarios, which in fact did occur throughout the country on election day. These actions were at great personal risk: There were 93 deaths on election day alone, a number of them NAMFREL volunteers.

Independent tallies showed a solid win by Aquino, but delayed official results from the official election commission declared Marcos the winner two days later. While the efforts of NAMFREL certainly did not prevent fraud, it drastically limited its scope. More importantly, it provided an opportunity for the world to understand the extent of the cheating and to demonstrate the determination of the Filipino people that the elections be fair. Similarly, the highly visible and risky walkout on February 9 by 30 of the 400 election commission workers over the government’s doctoring of vote tallies helped focus attention on the suspicious election results and allowed for increased domestic and international pressure for Marcos to resign.

The week after the election, nearly one million people gathered in Manila for a series of civil disobedience acts challenging the theft of the election. Their actions included boycotts of companies controlled by Marcos and his cronies, nonpayment of electric and water bills, and a general strike the day after Marcos’s planned inauguration. Many saw these moves as too modest and too late. Even these limited measures, however, led panicked Filipino elites to shift savings out of the country and the Catholic bishops to announce support for active nonviolent resistance.

The week after the election, nearly one million people gathered in Manila for a series of civil disobedience acts challenging the theft of the election. Their actions included boycotts of companies controlled by Marcos and his cronies, nonpayment of electric and water bills, and a general strike the day after Marcos’s planned inauguration. Many saw these moves as too modest and too late. Even these limited measures, however, led panicked Filipino elites to shift savings out of the country and the Catholic bishops to announce support for active nonviolent resistance.

A coup attempt by Marcos’s defense secretary and vice chief of staff of the armed forces along with reformist military officers on February 22 launched at Camp Crame and Camp Aguinaldo located on the main thoroughfare of Manila was supported by the opposition. Hundreds of thousands of Filipinos nonviolently surrounded the camps in the face of an expected assault by loyalist forces. Loyalist security forces with shoot-to-kill orders approached, but swayed by a sea of humanity, did not open fire and instead joined the coup. In the coming days, opposition forces seized broadcast stations and other important centers. On February 25, both Aquino and Marcos were sworn in as president in separate ceremonies, but the one for Marcos took place before only a small group inside his palace. He fled the country early the following morning after heeding the advice of Reagan emissary Paul Laxalt, a U.S. senator, who admonished Marcos to “cut and cut cleanly,” paving the way for Corazon Aquino to formally assumed office.

Serbia, 2000

Slobodan Milosevic had risen up the ranks of the Communist Party in Yugoslavia during the 1980s, but he increasingly embraced right-wing nationalism as he came into the leadership, leading Serbia into a series of horrific wars with neighboring Yugoslav Republics and in Serbia’s Kosovo region, for which he was later indicted for war crimes. Beginning in the mid-1990s, there was an active nonviolent movement challenging him and his alliance with right-wing ultra-nationalists. This movement, led by young people whose lives were shattered by the regime’s endless wars, supported a more pluralistic and democratic Yugoslavia and an end to human rights abuses against both Serbs and non-Serbs. In the winter of 1996-97, a mass nonviolent movement almost succeeded in overthrowing Milosevic, but it got no help or encouragement from Western governments. The Serbian government crushed the pro-democracy movement.

Students protesting the Milošević regime, 1996-1997. Source: Enacademic/Wikipedia (CC BY 3.0, unedited).

In 1998, a re-energized student-led pro-democracy movement, coalescing around a group called Otpor (“Resistance”), had emerged. Despite efforts by Milosevic to depict the opposition as Western agents, the vast majority of students involved were actually left-of-center nationalists, motivated by opposition to their government’s increasing corruption and authoritarianism, including the jailing and killing of opponents. Once the United States launched airstrikes against their country in 1999 in response to growing repression in Kosovo, however, they suspended their anti-government activities and joined their compatriots in opposing the NATO bombing. The U.S.-led war gave the Milosevic regime an excuse to jail, drive underground, or force into exile many leading pro-democracy activists, shutting down their independent media and seriously curtailing their public activities.

Not long after the war, pro-democracy forces led by Otpor were able to regroup. Using a variety of tactics, from demonstrations to street theater and other antics, they emerged as the center of the opposition, eclipsing even the leading opposition politicians who were often competing with one another. Otpor helped force most of the disparate opposition parties to unite as the Democratic Opposition of Serbia (DOS) under the leadership of Vojislav Koštunica, who was an uninspiring candidate but agreeable to different factions. The campaign then focused on rejecting another term for Milosevic.

Milosevic called for an early election, apparently concerned that his popularity would fall even further. The election was held on September 24, 2000. Results cited by DOS and two smaller parties the following day indicated that Koštunica had won a clear majority. The Federal Electoral Commission did not issue any statement until September 26, when they declared that Koštunica had fallen just short of the majority and thereby forcing a runoff against Milosevic. Noting discrepancies in terms of the numbers of voters and votes (which were later confirmed), the opposition declared the official result was fraudulent and a likely precursor to having Milosevic steal the runoff election. Going beyond simply street protests, the opposition escalated their noncooperation through a series of strikes and blockades, culminating in hundreds of thousands of Serbs from around the country peacefully assembling in Belgrade in front of the parliament on October 5, forcing Milosevic’s resignation.

Ukraine, 2004

Ukraine’s Orange Revolution, Kyiv, 2004. Source: Wikipedia (CC BY 3.0, unedited).

Since independence from Russia in 1991, Ukraine had been ruled by two corrupt and semi-autocratic presidents. Government thugs often disrupted the campaign activities of the opposition parties and engaged in numerous acts of violence, including the murders of a prominent opposition member Mykota Shkribliak and the poisoning of opposition leader Viktor Yushchenko, leaving him permanently scarred. Journalists who reported on corruption or criticized government policies were subjected to particularly serious harassment and violence; one prominent independent journalist was murdered. In the runup to the December 2004 election, the state-controlled Ukrainian media covered only the campaigns of pro-government parties.

A small protest movement had begun in the early 2000s with disparate elements, including liberal intellectuals, right-wing nationalists, supporters of the mainstream opposition party, and more left-wing youth disenchanted with the corrupt system as a whole. There were divisions among leading opposition politicians and a lack of trust of most major political figures by ordinary Ukrainians, yet there was a strong sense that there would be more hope for progress if Yushchenko could be elected and the ruling Party of Regions be removed from power. The incumbent president, Leonid Kuchma, who had been in power for more than decade, announced his decision to step down at the end of 2004 following elections, for which he endorsed his prime minister Viktor Yanukovych. Russia provided substantial assistance to the Ukrainian government while a number of international non-government organizations, some of which received some support from Western governments and foundations, provided support for pro-democracy groups.

Polling station in Dnipropetrovs’ka oblast’, 3rd round. Source: Wikipedia (CC BY 3.0, unedited).

A runoff election between Yushchenko and Yanukovych on November 21 was officially ruled in Yanukovych’s favor. Fraud was immediately suspected as the difference between exit polls and the official count was more than 14% in favor of the regime’s candidate and reports of intimidation of election monitors, ballot stuffing, multiple voting, and government pressuring of voters were widespread. Within days, half a million people had gathered at Kyiv’s Maidan Nezalezhnosti (Independence Square) and a series of acts of civil disobedience, sit-ins, and general strikes organized by the opposition movement swept the country. Local city councils went on record not recognizing Yanukoych’s claimed victory. Much of the Maidan area became an encampment, as hundreds of thousands continued to occupy the square despite extremely cold temperatures. The army refused to participate in a crackdown and warned loyal interior ministry troops that it would defend protesters. After over a month of protests, the results were thrown out by the Ukrainian Supreme Court on December 26 and a repeat of the election was ordered. The second vote took place on January 23 and Yushchenko was the clear winner.

Gambia, 2016

In 1994, Yahya Jammeh, a Gambian military officer seized power in a bloodless coup, overthrowing President Dawda Jawara, who had led the country since independence from Britain in 1965. For the subsequent 22 years, Jammeh suppressed dissent, including opposition media, and engaged in widespread human rights abuses. He particularly targeted the LGBTQ community, suppressed what he referred to as “sorcery,” claimed to have cured HIV/AIDS, cancer, and other diseases through herbs. He claimed he could “rule for a billion years” if God was willing. He had won re-election four times in what were generally regarded as unfair votes.

El País journalist José Naranjo was present in the Gambia to cover the 2016 elections and the #GambiaHasDecided movement. Source: Casa Africa/Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0, unedited).

Protests in the spring of 2016 were brutally repressed, with opposition activists arrested and killed, but they forced Jammeh to allow for a more transparent election process for the December presidential poll. In the runup to the election, which was to be decided by a plurality of voters, most of the opposition parties united behind businessman Adama Barrow, who campaigned on presidential term limits, an independent judiciary, and an end to human rights abuses. (The initial leading opposition candidate, Ousainou Darboe, a member of Barrow’s party, had been jailed by Jammeh.)

The December 1 vote declared Barrow the winner. While Jammeh initially appeared to accept the results, he reversed himself on December 9, insisted the vote was invalid, declared a state of emergency, and called for new elections. Protests broke out as Jammeh deployed troops into the capital and other cities. Barrow fled into neighboring Senegal as did thousands of other Gambians fleeing the repression. Many thousands more came out into the streets as the hashtag #GambiaHasDecided trended globally. The pan-Africanist group Africans Rising for Justice, Peace and Dignity helped the disparate opposition groups to heal their divisions and agree upon a unified course of action to ensure the election results were honored. Meanwhile, the Gambia Bar Association, teachers’ union, medical association, Press Union, Supreme Islamic Council, and others condemned Jammeh’s actions and supported the nonviolent resistance. A dozen serving Gambian ambassadors recognized Barrow as their president and called on Jammeh to step down.

The large-scale noncooperation and growing support for the unarmed resistance throughout Gambian society led neighboring African states to apply pressure on Jammeh to resign, eventually resulting in intervention by a multinational force from the Economic Community of West African States, which hastened Jammeh’s departure into exile.

Lessons

What the Filipino, Serbian, Ukrainian, and Gambian uprisings had in common to stop election subversion were:

- meticulous election monitoring and related efforts which enabled the opposition to make a convincing case that there was indeed fraud and there had not been a full and accurate count of the vote;

- mobilization of a large number of supporters within days when it became apparent that there were efforts underway to steal the election, building on networks of oppositionists which had been active for years;

- large-scale noncooperation challenging the legitimacy of the incumbent government, including popular contestation of public space, strikes, civil disobedience, and establishing alternative loci of power;

- strict nonviolent discipline by the opposition, even in the face of violent repression;

- the support of both the centrist political grouping whose candidate had been robbed of victory as well as grassroots elements of civil society to their left;

- loyalty shifts among regime allies, including noncooperation, defections, and desertions by government officials and security forces.

Should there be a serious attempt to subvert the results of the 2020 U.S. presidential election, these cases provide insight into how to uphold democracy. A government is only as powerful as the people’s willingness to obey. The above cases put that insight to the ultimate test, and show that even authoritarian rulers can be kept in check by a unified and determined population using a range of nonviolent tactics.